Proposal

Summary

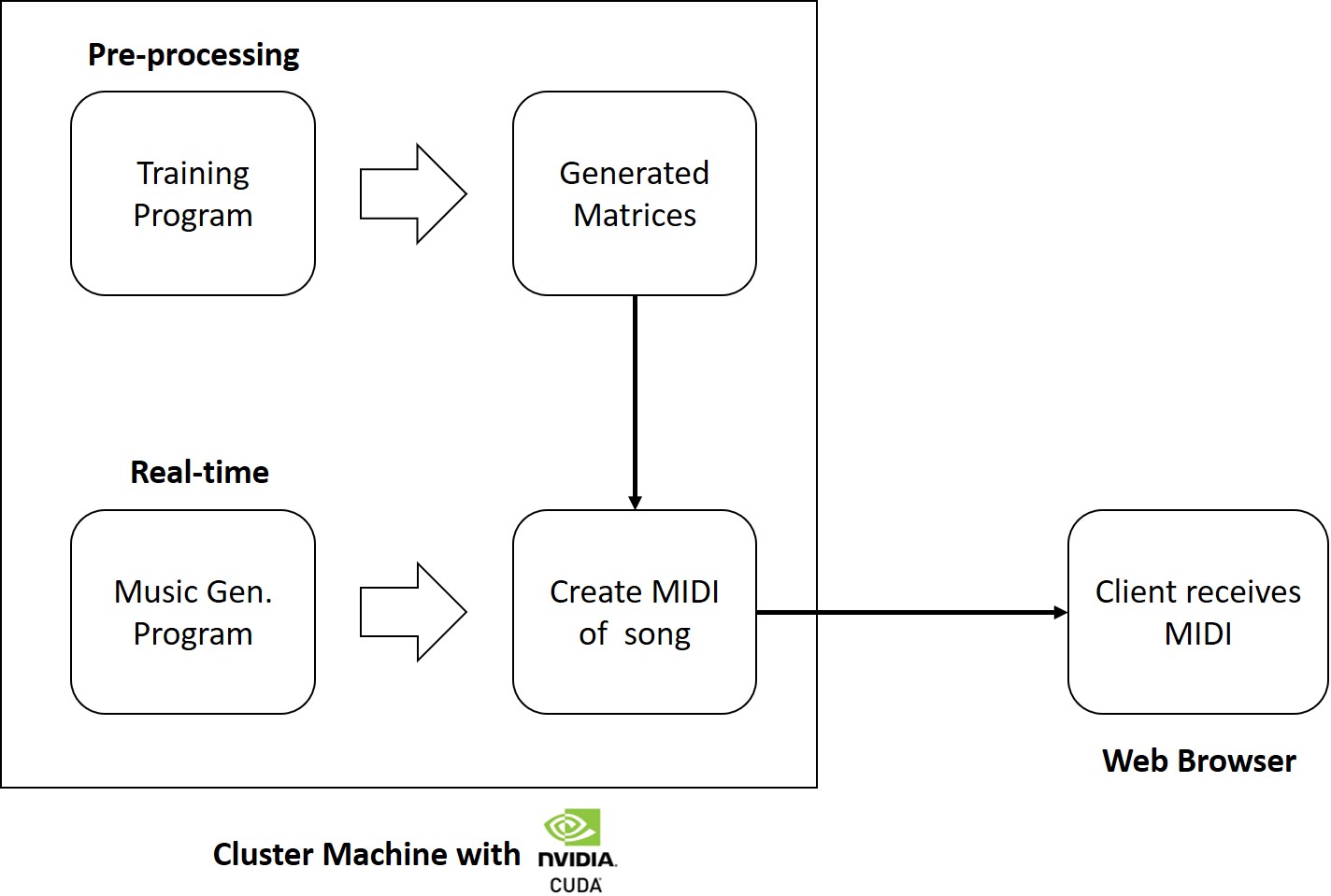

We will generate video-game music using a Markov Model based algorithm, with parallel computation through GPUs for real-time music output. We will be implementing parallel algorithms to analyze speedup for two portions of the project:

- Matrix generation: building the Markov matrices that will be used for music generation

- Music generation: parallel synthesis of multiple melodic lines using the trained matrices from matrix generation

Background

Through the forms and rules outlined in music theory, humans already follow many rigid guidelines when composing music. Therefore, it seems natural to extend this technique to using an algorithmic composer. In particular, the genre of video game music, which is characterized by the overlapping of multiple melodic lines and a repetitive and structured format, seems ideal as a starting point for parallel algorithmic composers. The many melodic lines offer ample avenues for parallelization, allowing for parallel synthesis of different parts. In addition, the rigid structure makes such music easier to predict and generate with a Markov Model — resulting in higher quality and more harmonious music.

The Markov Model of music generation was chosen for its popularity, good musical results, and ease of implementation, understanding, and parallelization. The model is easy to understand and implement, as it is based on using many probability matrices to determine the next notes of a melodic line. These matrices are easy to store and manipulate in many different programming contexts, including the GPUs we wish to use. Other music generation algorithms introduce too many new challenges, such as the recursive nature of Grammars (which may be difficult as it is not known beforehand how may recursions/threads we would need to spawn), or the poor music production of Structure and Probability techniques (Dannenberg, 2018). Finally, it has been shown that Markov Models produce good musical results, where computer compositions and human compositions had similar rankings in formal listening tests (Elowsson and Friderg, 2012). Therefore, implementing a Markov Model for our project would be the best choice for producing music with integrity and quality.

In a Markov Model, multiple matrices are built from training data, or files of music that fits the patterns and genre of the music we wish to create. Most commonly, this takes the form of counting the number of transitions from one note to another, and storing this count in a matrix. These matrices are then normalized and turned into probability matrices. For each melodic line, the algorithm uses the current (and perhaps some number of past) notes to determine the correct matrix and matrix row to look at. It then uses that matrix section to determine the next note, based on the probabilities in the matrix. Because the matrices are training on music of the same structure and genre, it is likely that the resulting melodies also follow the same structure and sound similar to the training pieces. The resulting melodies are then combined and outputted through MIDI.

Implementation

Benefits of Parallelism per section:

- Matrix generation:

- Matrix entries could be computed in parallel, as there are dependencies between entries. Since most entries hold counts for the number of transitions between 2 notes (determined by the row and column), these counts will be independent when notes are different.

- There will be many matrices for varying melodic lines — bass, melody, counter-melody, etc. These matrices can be computed in parallel.

- Generating weights based on varying levels of context (number of previous notes) require multiple data lookups that could perhaps be done in parallel.

- Training on multiple files can be read/processed in parallel, and then an overall reduction/sum may be performed in order to increase training performance.

- Music generation:

- Multiple melodic lines can be synthesized in parallel, allowing for faster generation of music, and perhaps leading to better performance. In addition, the increased speed, if significant, may allow for more complex or increased tempo in music generated.

Challenge

Although there are avenues for parallelization as seen above, music has many inherent synchronizational components that make it difficult to parallelize. For example, even if melodic lines can be computed in parallel, they need to sound harmonious when played together. Video game music often has theme changes that require concurrent operations, and all melodic lines must react in tandem to changes in theme, tempo, volume, etc. Although a parallel, faster algorithm for music generation could lead to more ability to generate complex, fast-paced music, the most basic requirement of music sounding pleasing to the ear forces a natural element of synchronization and therefore difficulty. We hope to explore this balance between the requirements on structure and harmony vs. the performance, speedup, and possibilities of complexity with parallelism, and determine how this balance affects the music we create.

What is hard

- Conductor: There must be something in charge of the overall direction of the music. This includes theme changes, dynamics, tempo, etc. This not only is many operations we have to keep track of in parallel, but also requires synchronization across all the threads being controlled by the conductor. E.g. if we transition from A to B theme, we need all the threads to be aware and transition at the same time. This creates many dependencies, and, in a shared memory model, a system of one writer and many readers to certain areas of memory.

- Melodic lines: There are many melodic lines happening at the same time. Generating them quickly requires parallelism, but also in order to make the music sound good, we need to make sure that the melodic lines communicate with one another to preserve harmony, chord sequences, and style. Again, we see that the harmonious nature of music create dependencies between parallel portions of the algorithm, and we need to balance the two.

Workload Characteristics

- Memory Accesses: When we are generating melodic lines, related melodic lines will depend on one another — for example, bass lines will be dependent on each others’ values in order to keep chords harmonious. Because of these relationships, there is some degree of locality. In addition, similar lines will access similar probability matrices. While accessing these matrices, since notes that are adjacent on the scale are more likely to be transitioned to, the lines may be accessing adjacent areas of the matrix over time. This is another area of locality. On the other hand, it is unlikely that the melodic line and the bass will need to access similar probability matrices, since they have very different structures and rules.

- Communication between lines: In order to maintain music theory rules and harmony, we need music generation threads to be aware of one another and make sure things are in check. This may result in a high communication to computation ratio, depending on how much communication is needed to keep chord and melodic lines harmonious. This is something we will be exploring during the project.

- Communication from conductor: The conductor needs to be able to look at what everybody is doing at all times. The conductor will mostly be performing reads on other data, and writes to a global data structure containing values that other people care about and read from. There are challenges associated to reducing contention when the conductor tries to write to its global structure while many other threads are trying to read from it.

Constraints and System Properties

- CPU to GPU to CPU: In order to output music, the CPU must transmit the final MIDI messages after receiving the computational results from the GPU. Therefore, we must set up communication between the CPU host and the GPU kernel, where the GPU performs the computations and melodic line generation, but the CPU performs the actual translation into MIDI and output.

- GPU computation: We need to figure out how to map our Markov model computations into CUDA and also how to convert the results into MIDI. We need to decide how to implement data structures and store the information needed to get good MIDI results.

- Web packets: We have to package our MIDI data into a web packet that can be comprehended by our client. In order to produce music, we will need to transfer the data from GPUs on the Gates machines to our personal laptops or other music generating device. This will be done through web packets, and introduces challenges in sending/receiving data as well as latency control (as the music must sound continuous).

Resources

In order to do the basic parallel computations on matrices and music generation, we want to use GPUs. Therefore, we need access to machines with GPUs. Our code base is essentially starting from scratch, with some guidance from 15418 asst2, where we used CUDA to process images. We will need to produce our own implementations of the various methods and structures to Markov models and training and generating music. We are using past computer music papers as references for building our Markov model for generating music (Dannenberg, 2018; Elowsson and Friderg, 2012). In addition, we need some sort of device to play the MIDI file. We are most likely going to use personal laptops, but we need to figure out how to write a program that can receive web packets and play MIDI in real time.

In terms of programming languages, we will be using Thrust, a C++ wrapper, in conjunction with CUDA in order to gain access to both GPU computation and MIDI (https://bisqwit.iki.fi/source/adlmidi.html C++ MIDI player). This allows us to have a familiar language that can satisfy the needs of the GPU computation and MIDI requirements.

Goals and Deliverables

We plan to create a video game music generator that produces music in real-time. The generator will first train multiple probability matrices in parallel over a large collection of files in the video game music genre, with significant speedup over sequential algorithms. Although it is dependent on the final model used, this training will most likely be based heavily on matrix sum operations and parallel reading into elements of a matrix. Therefore, we expect similar speedup goals as in general parallel matrix sum algorithms. For the second component, in musical synthesis, we plan to see significant speedup in the generation of multiple melodic lines. In the best case, this speedup would be linear in the number of melodic lines, although the many dependencies noted above may result in this being unlikely. Overall, we will produce a harmonious-sounding video game music parallel algorithmic composer that shows significant speedup in both training and synthesis over sequential versions.

We hope to create a Markov model that is more specialized in generating good video game music. Since we are focused on this one genre, we may make our algorithm more specialized in order to increase performance (either in runtime or musical quality). We would also like our application to be more widely accessible, which would require setting up a server and communicating to clients, most likely through a web browser.

Another stretch goal would be to demonstrate the feasibility of using parallel computation for video games in industry. For example, many soundtracks in video games are static and built-in, and thus don’t have much variation. Since video games already use GPUs, it would be interesting to see if music can have a role in using the GPUs in addition to the graphics which currently use them. We could explore the performance of using the GPUs to produce music with our algorithm in relation to the current method of producing music (static, built-in, sequential).

The demo will include speedup graphs that showcase the increased performance in utilizing GPUs over using sequential code. In addition, we will have live music generation during the demo that showcases our fast, parallel algorithm still produces a harmonious sound, showing we found solutions to the synchronization challenges noted above. The combination of melodious music and speedup graphs shows our understanding of the balance between dependencies in music and our parallel algorithm.

For the analysis component of our project, our algorithm will demonstrate significant speedup from utilizing GPUs, versus just using sequential code. This speedup may allow for more complex or faster-paced music generation. In addition, we hope to determine the balance between synchronization of melodic lines and conductors and parallel synthesis. Questions we hope to answer include how much communication is necessary to produce music-theoretically correct chords and harmonious sounding music, and how much synchronization and constraint a conductor places on music generation. Specifically, we hope to find quantitative ways to describe the balance between parallel synthesis of melodic lines and their interactions with each other and the conductor.

Platform Choice

We are planning to use the Thrust library on top of the C++ CUDA in order to write more efficient code. Thrust has significant performance benefits over C++, and also is easier to develop in, resulting in more productive development. In addition, the availability of MIDI APIs in C++ allow for us to use the same language in the final music output code.

Using GPUs to perform our computation is a good choice, as training and Markov Models use:

- Matrix generation: There are many elements of the matrix that can be computed in parallel, where each element does not require too much work.

- Matrix multiplication: This is a well-known problem that parallelizes well on GPUs. Also, like matrix generation, there are many small problems that can be done in parallel, which works well on GPUs.

Schedule

| Dates | Goal | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Nov 4 | Lit Review + Model | Learn about how MIDI is generated, and the various modifications to Markov Models and similar algorithms. Other research can include looking into video game music theory to properly determine the structure and rules we wish to follow. We want to decide on our model, determine why it works well, and what algorithm we will use to generate our music. |

| Nov 11 | Basic Parallel Alg. | Implement a CUDA program that generates matrices for our program. |

| Nov 18 | Music Generation | Implement the music generation part of our project so we can play generated MIDI files using the matrices trained from last week. |

| Nov 19 | Checkpoint | Summarize progress so far on project |

| Dec 1 | Optimize Music Generation | Optimize the music generation algorithm. Explore the balance between parallelizing melodic lines and harmonious output. |

| Dec 7 | Optimize Matrix Generation | Optimize the matrix generation, to speedup training time. Graph and analyze performance. |

| Dec 14 | Wrap-up | Complete final report |

| Dec 15 | Presentation | Practice presentation |

Works Cited

- Elowsson, A. and Friberg, A. “Algorithmic Composition of Popular Music,” in Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Music Perception and Cognition and the 8th Triennial Conference of the European Society for the Cognitive Sciences of Music, July 2012, pp 276-285

- Dannenberg, R. (2018). Music Generation and Algorithmic Composition [Powerpoint slides]. Retrieved from http://www.cs.cmu.edu/~./music/cmsip/slides/05-algo-comp.pdf